|

[ Outlaw Genealogy | Bruce

History | Lost Chords ] [ Projects | News | FAQ | Suggestions | Search | HotLinks | Resources | Ufo ] |

|

[ Outlaw Genealogy | Bruce

History | Lost Chords ] [ Projects | News | FAQ | Suggestions | Search | HotLinks | Resources | Ufo ] |

HogsBack stones are found where early Danes circa 900-1000 AD lived... They are referred to as "Viking" ... They do not have runes inscriptions so it makes it very difficult to understand them

Also although they are referred to as Grave Markers , as far as I know , no grave has ever been found with them. They may be memorials for those lost at sea, or bodies lost from war, or the graves had been robbed years ago.

Hogback (sculpture)

- are stone

carved Anglo-Scandinavian

sculptures

from 10th-12th century England

and Scotland.

Their function is generally accepted as grave

markers.

Hogbacks take the form of recumbent monuments, generally with a curved ('hogbacked') ridge, often also with outwardly curved sides. This shape, and the fact that they are frequently decorated with 'shingles' on either side of the central ridge, show that they are stylised 'houses' for the dead.

The 'house' is a Scandinavian type, and hogbacks are agreed to have originated among the Danish settlers who occupied northern England in the 870s after the fall of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria.

It has been suggested that the monument-type was invented about 920.

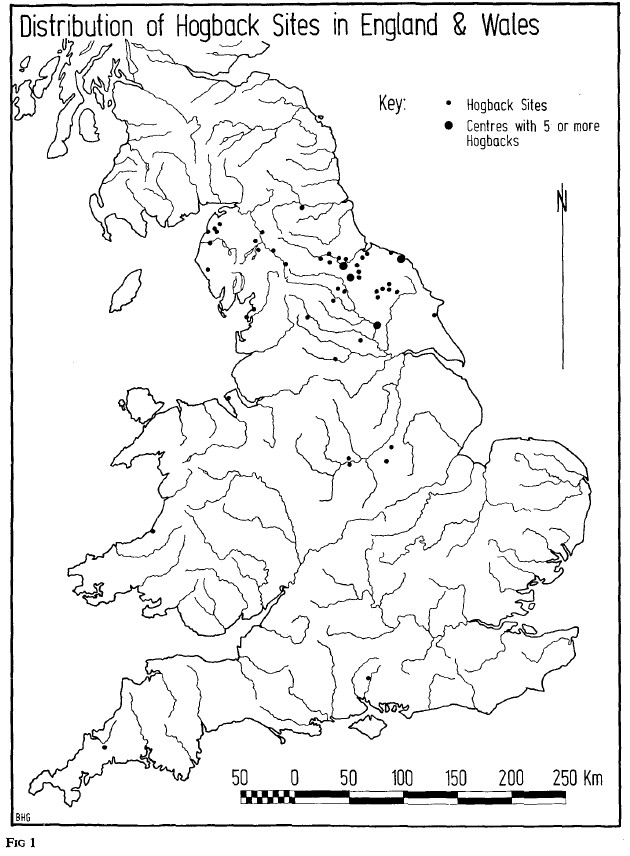

There are particular concentrations of hogbacks in Yorkshire and Cumbria, the former being their likely area of origin.

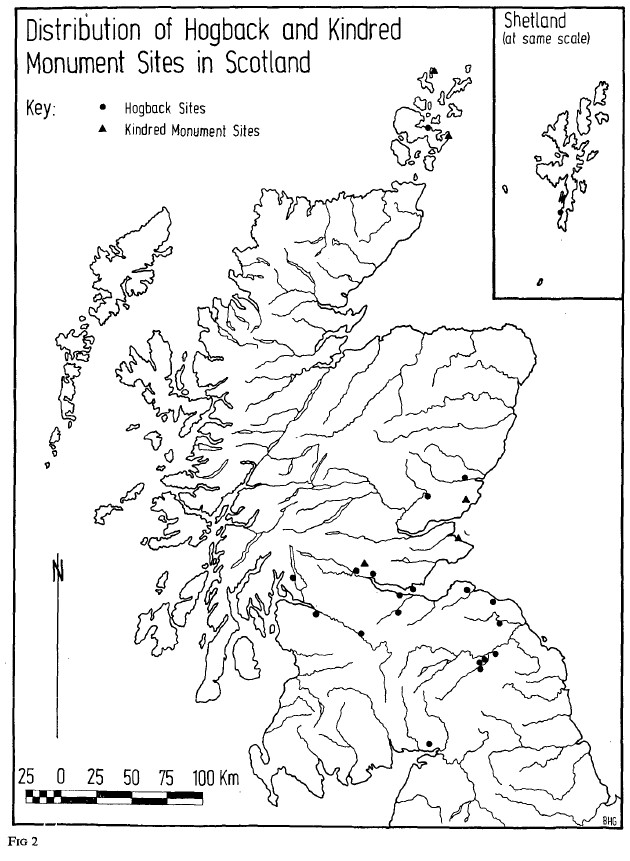

Individual examples are found over a much wider area, however, from Derbyshire to Central Scotland. There are stray examples as far afield as the Northern Isles, Orkney and Cornwall.[1] Ireland has a single example at Castledermot, Co. Kildare.

The most numerous collections are the ones preserved in St Thomas's church of Brompton, Yorkshire. Discovered in 1867 following the restoration of the church, six were taken to Durham Cathedral Library leaving four whole ones and fragments of others at Brompton. They are characterized by carvings of bears hugging the slabs with strapwork in their mouths. Elsewhere five are in the parish kirk of Govan, once a rural parish, but now part of Glasgow. There is a fine example in the visitor centre on Inchcolm island in the Firth of Forth.

St Peter's church, Heysham

English: Hogsback tombstone, St Peter's Church, Heysham (1) This was found in the churchyard and taken into the church for protection in the 1960s. It is a Viking stone of the 10C, and is possibly the best-preserved of such stones.

It is considered that this side depicts, in 'strip cartoon' form, the story of Sigmund. This is about his escape from wolves, and is too long to reproduce here, but can be obtained in the church. The overall design of the stone is an arched roof with a bear's head at each end.

Sigmund - In Norse mythology, Sigmund is a hero whose story is told in the Völsunga saga. He and his sister, Signý, are the children of Völsung and his wife Hljod. Sigmund is best known as the father of Sigurð the dragon-slayer, though Sigurð's tale has almost no connections to the Völsung cycle.

In the Völsunga saga, Signý marries Siggeir, the king of Gautland (modern Västergötland). Völsung and Sigmund are attending the wedding feast (which lasted for some time before and after the marriage), when Odin, disguised as a beggar, plunges a sword into the living tree Barnstokk ("offspring-trunk"[1]) around which Völsung's hall is built. The disguised Odin announces that the man who can remove the sword will have it as a gift. Only Sigmund is able to free the sword from the tree.

Siggeir is smitten with envy and desire for the sword. He invites Sigmund, his father Völsung and Sigmund's nine brothers to visit him in Gautland to see the newlyweds three months later. When the Völsung clan arrive, they are attacked by the Gauts; King Völsung is killed and his sons captured. Signý beseeches her husband to spare her brothers and to put them in stocks instead of killing them. As Siggeir thinks that the brothers deserve to be tortured before they are killed, he agrees.

He then lets his shapeshifting mother turn into a wolf and devour one of the brothers each night. During that time, Signý tries various ruses but fails every time until only Sigmund remains. On the ninth night, she has a servant smear honey on Sigmund's face and when the she-wolf arrives, she starts licking the honey off and sticks her tongue into Sigmund's mouth, whereupon Sigmund bites her tongue off, killing her. Sigmund then escapes his bonds and hides in the forest.

...

| - - - --

Signy - or Signe (sometimes known as Sieglinde) is the name of two heroines in two connected legends from Scandinavian mythology which were very popular in medieval Scandinavia. Both appear in the Völsunga saga, which was adapted into other works such as Wagner's 'Ring' cycle, including its famous opera The Valkyrie. Signy is also the name of two characters in several other sagas.

The first Signy is the daughter of King Völsung. She was married to the villainous Geatish king Siggeir who has her whole family treacherously murdered, except for her brother Sigmund. She saves her brother, has an incestuous affair with him and bears the son Sinfjötli. She is burnt herself to death with her hated husband.

| =- = = = =

Viking Grave Slabs at Heysham Head - YouTube

Giants Grave Penrith:

The Megalithic Portal and Megalith Map

Giant's Grave, Penrith - YouTube

The Giant’s Grave, Penrith, Cumbria The Journal of Antiquities

The two tall and slender pillar-crosses standing 15 feet apart are now heavily worn and it is difficult to make out the carvings on them, but they have been dated to around 1000 AD and are Anglo-Norse in origin. Both crosses have sustained some damage – the taller cross with a badly damaged head is between 11 and 12 foot high, while the smaller cross, also without its head is between 10 and 11 foot high. Set between them, spaced 2 feet apart, and embedded into two long slabs are four hogback gravestones with curved upper edges and some rather nice carvings, including spiralling and circles with crosses or interlacing inside them. These graves represent Viking houses with carved sections depicting the life of the person(s) buried beneath them, often with intricate symbols and patterns; the stones here may represent four wild boars killed by king Owain in Inglewood Forest.

A collection of Hogback Stones in the church of St Thomas, Brompton, Yorkshire. These stones, which date back to the 10th to the 12th centuries are grave covers. These examples show bears gnawing at stylised roof structures - no one is sure why. Generally it is boars (hogs) doing the gnawing!

Excellent video about the Hogbacks - this rare one found in Kildare Ireland - (only one in Ireland!)

Hogback Gravemarker, Castledermot, County Kildare - YouTube

Hogback Grave Marker at Luss, Scotland - YouTube

Tour of Glasgow Scottish Tour Guide's Blog

Next we headed into Glasgow to visit Govan Old Church. Like Luss the current church is late 19th century but situated on a very ancient Christian site. Inside can be found a collection of 9th/10th century carved stones with Pictish and Viking influences. We were treated to superb hospitality by church representatives and provided with a tour of the church and stones.

England >> Cheshire >> St Bridget (West Kirby)

A Viking hogback fragment, and cross fragment, inside St

Bridget's West Kirby.

West Kirby - is a town on the north-west corner of the coast of the Wirral Peninsula, in the county of Merseyside, England, at the mouth of the River Dee across from the Point of Ayr in Flintshire, Wales. To the north-east of the town lies Hoylake, with the suburbs of Grange and Newton to the east, and the village of Caldy to the south-east. ...

The name West Kirby is of Viking origin, originally Kirkjubyr, meaning 'village with a church'. The form with the modifier "West" exists to distinguish it from the other town of the same name in Wirral: Kirkby-in-Walea (now the modern town of Wallasey). The earliest usage given of this form is "West Kyrkeby in Wirhale" in 1285.

The old village lay around St. Bridget's Church, but the town today is centred on West Kirby railway station, which is about 1 km away

It is likely that there was a church on the site before the Norman Conquest. The first stone church was built around 1150–60. In the 13th century there were alterations or a rebuilding

Hogbacks - Zeugnisse akkulturieter Migranten Kerstin P. Hofmann - Academia.edu

"Various theories concerning cultural change underpin the Humanities and

the Social Sciences. Currently, one of the most widely accepted models within

German prehistoric archaeology revolves around the concept of acculturation, a

term originally developed in the fields of sociology and cultural anthropology.

However, the application of this explanatory model of cultural change to a set

of specific historical circumstances is accompanied by certain limitations.

Firstly, the holistic concept of culture employed within this particular notion

may provide the incorrect assumption of the existence of a series of

hermetically sealed entities. Secondly cultural exchange is a permanent ongoing

phenomenon. Finally, there is an underlying bias of Eurocentric unilaterality.

Identity, when examined from the perspective of being both complex and

referential, provides for the avoidance of this idea of unaffected, airtight

‘units’. Situations of contact with foreigners appear as the only contexts

that can be reasonably investigated, with mobility therein held as a base

premise. Historicity can be more suitably explained for example by the

application of Urs Bitterli’s (1986; 1991) classification of culture contacts

or through innovation-theoretical considerations. The application of Ortiz’s

(1940) concept of transculturation teamed with the inclusion of approaches

founded in post-colonial studies can preclude seemingly one-sided

investigations.

After such modification, the concept of acculturation better satisfies current

requirements. By way of illustration it is to be applied here to the

archaeological find category of hogbacks, house-shaped stone monuments of the

Viking Age with convex sides and occasionally end-beasts found in Great Britain

and interpreted as grave stones. Already, James T. Lang in his publication

“The Hogback. A Viking Colonial Monument” (1984) has pointed to their

relevance as sources for the Scandinavian colonisation of the British

Islands.

A total of 144 of these stones have been preserved, yet their original find contexts are unknown. Beside their spatial localisation, their other mutually interrelated components – technical execution, shape, ornamentation and iconography – are significant for their interpretation.

Against the background of the historically and archaeologically recorded relations between the British Islands and Scandinavia, stylistic analysis of the hogbacks enables them to be construed as material expressions of migration. They likely originated during the establishment of Norwegian immigrants in Yorkshire after they had been driven out of Ireland in the second quarter of the 10th century. The stone sculptures thus dispersed in Ireland and the British Islands are mostly unknown in Scandinavia. Furthermore, Scandinavian, Anglican and Irish elements are united into a new art style in their ornamentation. Therefore, the hogbacks are to be seen as resulting from a process of acculturation. Being an mental innovation, they could have been used as a means of locating one’s own identity as well as a way of legitimating power in the confrontation with other groups."

SCANDANAVIANS AND SETTLEMENT IN THE EASTERN IRISH SEA REGION DURING THE VIKING AGE

Hogbacks of Gosforth

Finally, the chapter details the unique sculpture of the region, which is Anglo-Saxon and

Christian in form but thoroughly Scandinavian is style and motifs. The largest and most obvious

example is the Gosforth Cross. But there are other examples of note, including the unique

“hogback” monuments, which are mostly pagan Scandinavian in theme, and are not located to

any extent outside of this particular region. They almost certainly show another expression of

the form in which the two cultures merged to form a new, Cumbrian-Scandinavian culture in the

region.

Heysham: ... Viking ‘hogback’ burial monument was discovered at this same church in circa 1800. Its relation to the grave, if any, is unknown. Two Scandinavian objects at the same site are significant, however.

Penrith: The Cumbrian parish churchyard in Penrith is best known as being the home of the

so called “Giant’s Grave”, the rectangular arrangement of four pieces of hogback stones and two

Viking period crosses. The pieces had been moved several times before their appearance in the

written records of the seventeenth century, and excavation in the nineteenth century showed the

site to be much disturbed. A folk tale exists telling of its opening, and tells of an inhumation

grave accompanied by a sword. The tale, of unknown age but possibly from the seventeenth

century, seems to suggest a grave of a single individual only. This grave also bears the mark

of possible Scandinavian burial.

There is a significant history of stone monuments particularly in the

northwest of England and the Isle of Man, and a smaller tradition in Scotland.

There is on the whole too much of this material to be described in detail, with

there being some 170 catalogued objects in Galloway alone, but several particular sites—Gosforth in Cumbria, for instance, stand out as of greater importance and are worthy of extra attention. There are a few pieces of stonework in southwest Scotland that perhaps offer some cryptic hints of settlement, and a rich tradition of stone carving on Man. Stone carving can generally is meant to mean stone crosses, which may or may not be indicative of burial, as well as other forms of monuments,

most specifically the so-called hogback monument, which will be discussed below.

...

Arguably the most important, symbolic representation of Viking period sculpture is a type of stone structure commonly called a hogback. The distribution of the hogback monuments is limited. They are confined to northern England and central Scotland, with Ireland and Wales having but a single example each. There are a few later kindred monuments in Orkney, but none of these are found on Man despite its strong tradition of stone working. Iceland lacks them completely, while the other Scandinavian countries have a similar but later tradition of Romanesque that seems to have developed from the earlier-- British style. The inspiration for the creation of these carvings is a matter of great debate, and probably cannot ever be convincingly answered beyond any reasonable doubt.

Essentially, the hogback is a large stone monument which strongly resembles an overturned boat in its shape. They are often over a meter in length and, while they show regional diversity, their particularly Scandinavian design places them firmly in the Viking period

Unlike contemporary crosses, there is no doubt that these monuments were contemporary grave markers, evidence for this function being found in the archaeological record at Heysham, Brigham, and Penrith, Cumbria. Also unlike the crosses, most of the hogbacks lack the appearance of obvious Christian iconography.794 Out of an enormous variety of hogbacks, only a very few, including the so-called Saint's Tomb inside Gosforth church (crucifixion scene), contain any Christian iconography.795

There is at least one instance of a possible crucifixion scene on a hogback forming part of the Giant's Grave at Penrith, but the inscription is no longer

discernable. James T. Lang, "The Hogback: A Viking Colonial Monument," Anglo-Saxon Studies in Archaeology and History 3 (1984), 87. The absence of such structures on Man is perhaps surprising, given the tradition of stone crosses and Scandinavian settlement on the Isle. It has been suggested that the geology of the Isle is rather different from that of northern England. Their absence is better explained by the fact that

the slate stone of Man is ill-suited to the production of these large, three dimensional

monuments, rather than that the Isle of Man was somehow isolated from the rest of the region. See Richard N. Bailey, "Aspects of Viking-Age Sculpture in Cumbria," 55. It is possible there may be a few others, since there are some examples that are badly worn. But the overall impression is that Christian iconography is quite rare.

...

The unique nature of the hogback and its firm dating to the Viking period make it an especially valuable tool for understanding the cultural interaction and negotiation being carried out in the regions where it is found. The use of the hogback tombstones is not native to either the immigrant or the receiving population. It would seem that it could be seen as an extremely visible, iconographic representation of the assimilation of the two communities in the context of a cult practice that was in use at the time.

Unlike graves, which may or may not be in a known location, these monuments were highly visible and were probably meant to be permanent, and they were not

inexpensive. It follows that there were patrons who were well-placed in society to commission the buildings of these monuments, and that there were sculptors skilled enough to carve them who also had knowledge of Scandinavian motifs and

styles. It seems further to be a necessity that the local populace, including Church officials, would give consent, since many were erected in sacred

space.

Abrams.doc - The University of Nottingham

Hogbacks are not found in all areas of Scandinavian settlement in Britain and Ireland. The distribution map reveals some interesting blanks. There are no known hogbacks in Northumbria much north of the Tees (though there is a cluster along its northern bank), nor in southern Yorkshire, Lincolnshire, East Anglia, or the midland areas of the Danelaw. There is only one in Ireland, and none are found in the Hebrides, Galloway, or the Isle of Man, despite the latter having more runestones than anywhere outside Scandinavia. There are (now) two in the Wirral, and several Scottish examples in addition to the five hogbacks ‘of Texan dimensions’ preserved at Govan in Strathclyde; but Bailey has described hogbacks that occur outside the concentration in Yorkshire and northwest England as ‘eccentric in their form or decoration or [dependent] on northern English models’. The hogback clearly had an influence on the design of recumbent grave slabs, so it is sometimes difficult to decide whether an example properly belongs to the hogback category. As Lang explained ‘the outlying hogbacks are usually modifications of the local shrine tomb type with ornamental overtones from the hogback repertoire.’ The five in Orkney, for example, have been described as ‘kindred monuments’ and are thought to be later imitations of hogbacks seen elsewhere by their patrons. Lang likewise considered the few in the North Midlands (Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire) to be late and influenced by the Yorkshire monuments.

There are regional variations within the class of monuments, involving both form and ornament. The tall narrow type seems to be a western phenomenon, found mainly in Cumbria. The Illustrative Type, so-called by Jim Lang, is also found most commonly in northwest England, and many hogbacks from that region have a snake hugging the bottom or top of the monument. The large clasping bears feature mainly on Yorkshire hogbacks.

Bailey has explained the absence of hogbacks from the Isle of Man by geology: the kind of stone required was not available there. This explanation could be extended to some areas of England, such as East Anglia, which lay outside good sources of

suitable stone, but it would not (I think) apply to all the midland areas of Scandinavian settlement. More geological analyses of surviving examples would help determine whether their general differences of form can be explained by local (or indeed imported) geology. Other, less practical, reasons have been found for the fact that hogbacks are not found everywhere that Scandinavians settled. The lack of Irish hogbacks, for example, has been attributed to the different circumstances of Scandinavian settlement there (more limited to the towns and their immediate hinterlands) and to the continuing strength of traditional ecclesiastical (especially monastic) centres. In the English Danelaw, changes in patronage, due to the decline of many religious institutions, and the more rapid assimilation of Scandinavian settlers than in Ireland, would have made conditions quite different for new Christians, and, as we shall see, their independence has been credited with affecting more than fashion in sculpture. The absence of hogbacks north of the Tees has been explained by the survival of a native dynasty at Bamburgh, associated with the community of St Cuthbert, and their success in keeping Danish settlers at bay.

The most common ‘historical’ explanation for the distribution, however, has been the association of hogbacks with the Hiberno-Scandinavians who left Ireland for England in the early tenth century. James Lang made the important observation in the 1970s that hogback distribution coincided with regions in England where ‘Norse-Irish’ place-names were to be found. The Hiberno-Norse left a much stronger imprint on the place-names west of the Pennines, where we find wholly Irish names, Irish loan-words, and ON place-names in Irish word-order (i.e., Aspatria, ‘Patrick’s ash’). But there are examples in Yorkshire as well: Fixby (West Yorkshire), Melmerby (North Yorkshire), and Duggleby (East Yorkshire) each contain as first element an Irish personal name – Fiacc, Maelmuire and Dubgilla [Dubgall?], respectively.

This link has been used to date the hogbacks after 920, a date supplied by written sources which record the expulsion of Scandinavians from Dublin in 902, and the activities of those members of the ruling family from the second decade of the century who made themselves kings of York.

While Anglo-Scandinavian sculpture of all kinds, including hogbacks, is indeed a feature of these regions, it is nonetheless usually found in settlements with English, not Scandinavian names. The correlation between names and sculpture is therefore not a simple one.

Because they are found at church sites, often reused as building material, hogbacks are almost universally seen as Christian funerary monuments. Their similarity to shrine-tombs would suggest that they shared a function of commemorating the dead

(as does the apparent influence of the sarcophagus form). On the other hand, no hogback has been found in association with a grave, with the possible exception of the monument from St Patrick’s chapel, Heysham (Lancashire), and the hogbacks from Penrith. (It is, however, unclear to me how many have been found in situ: apparently very few, and then mainly in the nineteenth century, when circumstances were far from ideal in terms of excavation technique and the preservation of information about the context of their discovery.)

Hogbacks have been described as a secular response to the saints’ shrines found in contemporary churches, and it is worth considering whether this response need have indicated conversion to the religion of those churches. Could hogbacks, alternatively, have begun as a pagan imitation, monuments looking to express identity for a group of outsiders in a form with a contemporary and local resonance, but without a commitment to the local religion? This interpretation has received some encouragement from the motifs present on Lang’s Illustrative Type.

The Lowther, Gosforth, and Sockburn hogbacks, for example, are decorated with mythological scenes and symbols, some of them quite obscure. Lang linked the visual portfolio of warriors and beasts to Gotlandic warrior funeral iconography, arguing that it probably came to Britain from (pre-conversion) Scandinavia on textiles, shields, and other wooden carvings, transferred from these perishable media to stone thanks to the influence of local stone-raising habits.

Sockburn, for example, ‘depicted many of the traditional stories and motifs of the Scandinavian homeland and of pre-Christian belief’. Some of the symbols and motifs on these hogbacks, like the triquetra and the triangular banner, recur on coins of York’s tenth-century kings. In contrast to the Gosforth Cross, however, these monuments are ‘not so clearly oriented towards a Christian message’, because their mythological motifs are not matched with Christian images.

It may therefore be questioned whether hogbacks were always Christian. It has been observed that paganism, towards the end of its existence, borrowed elements from the rival religion in order to compete more effectively or to show itself to better effect. The presence of Scandinavian monuments without explicit Christian symbols in churchyards need signify no more than that those burying the Scandinavian dead did

so in those sites already populated by the (deceased) elite of the region. By taking over these burial sites the new Scandinavian lords could have indicated that land (and title to land) had been taken over as well. Burying your dead in someone else’s churchyard would have been an excellent way of proclaiming and embedding your claim to their property and social position.

Most hogbacks lack any suggestion of Christian symbolism, although there are one or two with crosses or crucifixion scenes (not always easily identifiable as contemporary with the original ornament). Some, such as those at Lythe (North Yorkshire), have been found with a collection of smaller stone crosses which, Bailey has argued, fit the undecorated gable-ends of the hogbacks and could have acted as head- or foot-stones. These would therefore appear to be more clearly linked with a Christian identity. At present, it is unclear where the hogbacks with explicitly Christian motifs fit into the chronology of the series.

Alfred Smyth judged the hogbacks ‘as a class … to be essentially non-Christian in character’, suggesting that

the house shape could have been a representation of Valhalla. David Stocker, on the other hand, has argued that the monuments represent a distinctive, hybrid, religion practised by the Scandinavians which was characterised by ‘the acceptance of the Christian god into the pagan pantheon’.

The settlers incorporated ‘Christian figures into Norse paganism’, a development sanctioned by the archbishop of York and promoted particularly in Deira, under his aegis. Stocker believed this half-and-half religion developed from the beginning of Scandinavian settlement

Hogback monuments in Scotland.pdf

---- >>> Back to Outlawe Index